Weekly Forecasts 40/2025

The trouble with the U.S. federal deficit, and banks

The fiscal balance of the U.S. federal government sinks further.

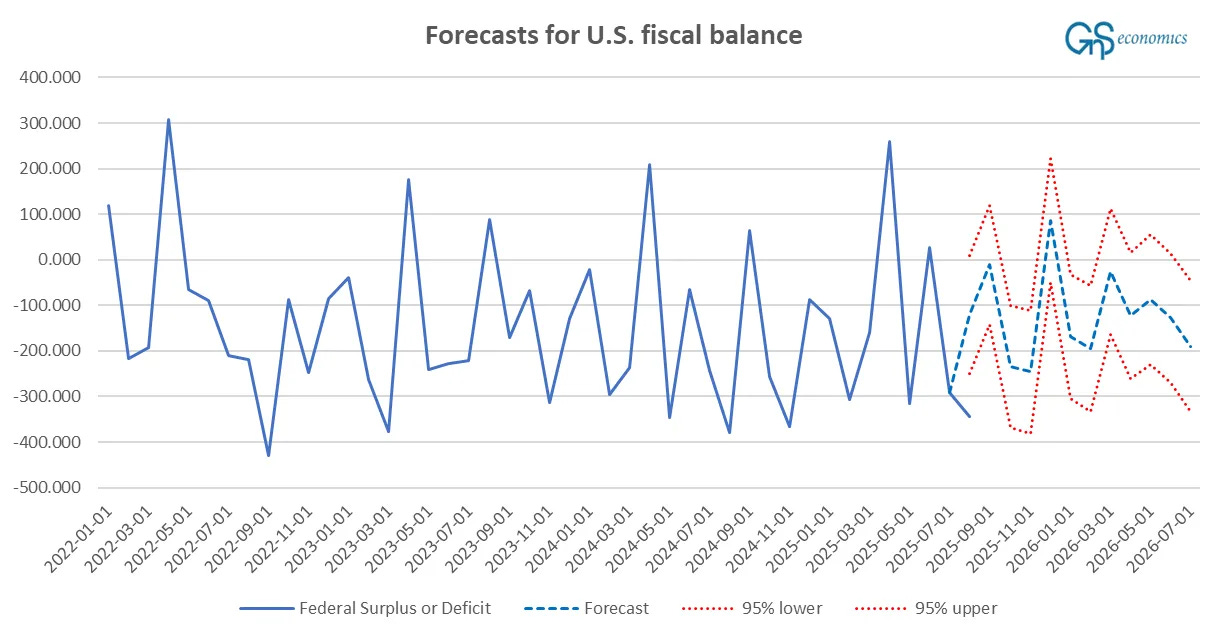

Forecasts for the U.S. federal budget balance.

The banking sector of the U.S. strengthens and weakens at the same time.

This week we concentrate on the U.S. federal fiscal balance and developments in the U.S. banking sector. Our forecasts failed to anticipate the sinking of the U.S. fiscal balance over the past month. The missed decline did not come as a major surprise, though, also because our model for forecasting the U.S. fiscal deficit is in its infancy. The updated model continues to indicate an improving federal fiscal picture of the U.S., a result that we should take with healthy skepticism.

We also return to analyzing the situation of the U.S. banking sector. There was a pause because we did not think updates were needed, as there were no major banking troubles, and because we have been rather overwhelmed with different projects. Now this pause ends, and we will provide a brief update on the overall situation in the U.S. banking sector before returning to bank-to-bank analysis in the coming weeks. Our analysis indicates that the U.S. banking sector has turned both more robust and more risky at the same time.

Tuomas

Federal fiscal deficit jumps

At the end of August, our (preliminary) forecasting model anticipated that the fiscal deficit of the U.S. federal government would have been $199.936 billion in September. The deficit turned out to be much worse: $344.792 billion. Our forecast missed this “sinking” completely.

Figure 1 shows that the federal deficit blew past even the 95% confidence intervals of our forecasts. This underlines the challenge of producing reliable forecasts from the fiscal balance. Like we noted at the end of August:

The interpretation of the former [chaotic autocorrelation of the fiscal deficit series] is not straightforward, but the fact that autocorrelation seems to die and return over a long period of time hints at the possibility that decisions (deficits and surpluses) from a long time ago affect decisions in the now, but somewhat randomly (in time), which is a plausible assumption. This “chaotic” nature of autocorrelation will complicate the time-series analysis of the fiscal balance series.

Simplified, we argued that the history of the series implies that deficits from far (several months or even years ago) seem to affect the decision made now. What we can add to this now is that the fiscal deficit turns ever more chaotic after 2020. Essentially, the ability of our model (described below) to distinguish and thus forecast the changes in the series deteriorates notably after 2020. In statistical terms, we notice that the variation in the residuals (essentially in the forecasting errors of the model) grows notable in 2020 and stays elevated all through 2024. This implies that something major happened not just with the U.S. federal fiscal deficits but also with the decision of how they are made.

Forecasts for the U.S. federal fiscal balance (second attempt)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to GnS Economics Forecasting to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.